27 Hours Aboard Ingeborg: Maintenance, Stories, Lessons and Relaxation

But, no fish!

[Image: The skipper at peace.]

Publication date: 2022-08-23

Update 2022-10-18: an addition of a quote from “On Seamanship and Seafaring” is added.

Preface

This article relates in several manners to an earlier article about gifts and another skipper, my father. The little I’ve learned about maintaining a foredeck is mentioned there, as are the responsibilities of a skipper. The “Around Sjælland” race mentioned below is the Annex to this preceeding article.

This article contains even more yachting terms. Some attempt at explanation is made, in parts.

An Invitation

There was a nice breeze forecast, with good weather and some work to be done. On the evening before, as we enjoyed a norweigan dried fish which Lamberto had soaked for a week and prepared with an Italian recipe, he invited me to accompany him aboard his yacht, the sloop Ingeborg for a little cruise.

Lamberto was up early and had already done some maintenance when he collected me. We spent half an hour acquiring victuals for the trip before arriving at the marina.

[Image: to the starboard side, just in the cabin are the communications equipment. Below can be seen hand written instructions for use in emergency situations, including calls signs and channel numbers. To the right is the view forward in the cabin. Atop the bulkhead can be seen 4 instruments, a clock, barometer, hydrometer and thermometer. The light blue, with two red stripes, bag contained the number 1 headsail.]

Another two hours would be spent performing maintenance and easing the handling of the vessel before we left Helsingør's marina. The first task was a once in three year operation which turned out to be more frustrating than hoped. The constant pressure on the rubber seal surrounding the propeller shaft as it passes through the hull means that sea water, slowly but surely will leak into the bilges. To prevent this a spring loaded tube filled with a thick grease serves to push back against the pressure and seal small gaps that may develop. Over time this grease leaks and needs be replaced. With a fair amount of thought, quite some "elbow grease" and a tad of frustration, the task was completed by the skipper.

During the recent weeks Lamberto had demounted the furling headsail which had come with the boat when purchased years earlier. The new choice was a small collection of standard headsails to be clipped to the forestay; a traditional setup. There is, however, a limitation on this 1969 fibreglass 27 foot sloop. The headsail halyard terminates at the mast and there is no winch yet fitted there. Thus, raw muscle power would be the only way to tighten the headsail's luff (the sail's edge attached to the forestay). For the number one sail, the largest, this would never be effective, and that was the sail which we would deploy.

The initial solution was a pulley system to be attached via a cleat on the end of the halyard and to the plate at the mast’s foot. Trial showed that the intended solution would not work without a hook attached from the cleat to the halyard to the keep the cleat aligned, and thus the halyard in its grasp. The solution to this problem was Lamberto inverting the ineffective solution. Why not attach the base pulley to the plate at the base of the forestay? Then the top pulley could be attached to the tack (lowest leading corner) of the headsail. Voila! Up the headsail would go, and then be tensioned at the bow rather than at the mast. It had the addional benefit that it does not clutter the mast. Apart from the safety rail, the bow of the boat hosts only the forestay and anchor, with the two cleats for securing her in harbour. Thus, the addition of the pulley based downhaul there, would fit nicely.

[Image: the image was taken upon return, but shows the foredeck as it was when we left. From the center left can be seen the change in colour of woods of the gunnels. I had assisted Lamberto with removing the old gunnels, and together we measured and marked most of the new wood the weekend before. He fashioned and installed these new gunnels. In the bottom to centre right can be seen the equipment on the bow. One of the two open cleats is visible securing Ingeborg. The anchor is secured. Both items secured to the plate on the bow, the forestay, and downhaul can be seen attached. Moving up, we see the downhaul secured to the headsail halyard.]

The time was approaching 14:00, the late summer weather was warm, and we had a nor'wester of 10 knots gusting to 15. Having motored from the marina's harbour, off the Kronborg "castle" the engine was disengaged, and the sails hoisted.

[Image: Kronborg. The image was taken on our return journey, as we were a little busy hoisting sails heading out. As you will see in later images, the sky on the day was nearly clear blue.]

The mainsail was newer than that which we'd used three years earlier in the "Around Sjælland" race. Lamberto had installed additional reefing points on it too. With the newly installed downhaul for the headsail applied, its luff held lovely tension.

We ran, gybing downwind all the way from Kronborg to the Swedish island of Ven (pronounced Veeen) which was only 10 or so nautical miles away. We regularly hit Ingeborg's top "regular" speed of 6 knots, sitting in the cockpit enjoying the beautiful weather and view, and each others company.

[Image: At the top, the foot of the mainsail and the wooden boom can be seen. On it what I believe is one of the reef lines can be seen. To the right the foot of the number one headsail can be partially seen.]

[Image: A close up of two older wooden hulled, multi-masted vessels enjoying the good breezes and lovely weather seen in the background of the above image.]

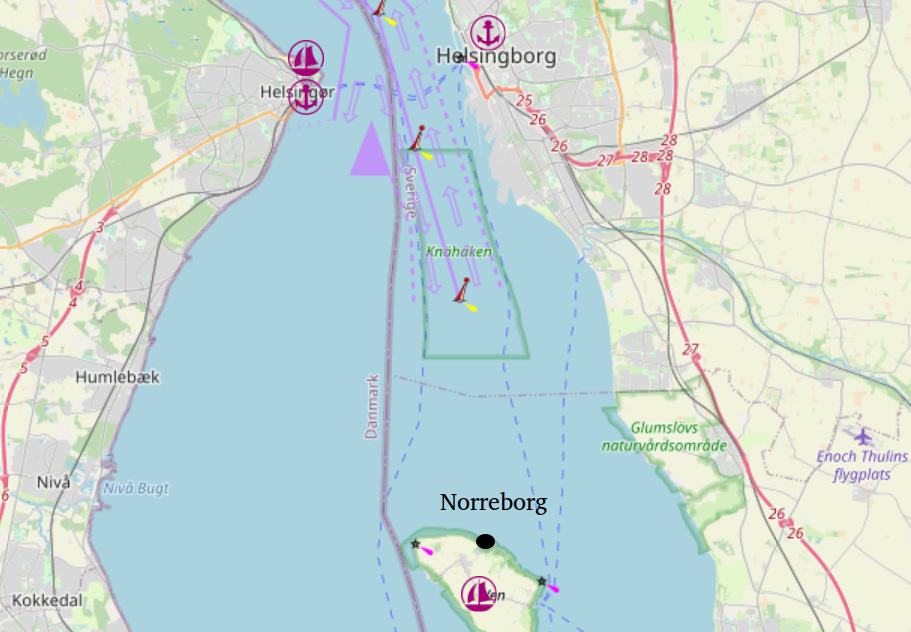

The trip was 27 hours from start to end, including a too noisy evening (not us!) in the Norreborg harbour at Ven.

[Chart: the location of Norreborg harbour is added to this image from OpenSeaChart.]

Despite a few years of sailing, mostly in racing form, I am sad to admit that there are many simple knots which I have yet to master. I have the absolute core essentials of the bowline and reef, with the slip release half hitch. There are other, trivial knots which I am still learning. For example the one used to securely fasten a fender to the safety line, and the optimal way to secure cordage on open cleats. This last may not be a knot, but a careful technique which ensures that strain is applied to the open cleat directly, the fastening will not slip, and is still easy to release. Skipper Lamberto's calm and patience were on display as many a lesson was offered on these and other topics.

If there was one major failure I committed, it was a cardinal sin. In an earlier article on being a foredeck crew I wrote:

If there is a mantra for the foredeck, it is this: Order.

I failed to properly tidy the headsail halyard. It was fastened securely on the mast, but its long tail lay below in an untidy mess. As we approached the Norreborg harbour, we needed to drop both sails, beginning with the headsail. Lamberto was watching my progress of making order of this line as I declared "I'll need two minutes." The reply came, "you do not have two minutes.” Technically, I made a similar mistake on the return journey, by not lashing the dropped headsail. Again, due to calm conditions, there was no problem. But, that is not the point.

This was lazy work, or actually not doing the work. It was all fine in the end, but that is because the weather was good and sudden violent storms do not really occur in the Baltic as they do in the Mediterranean.

With sails dropped and secured, and the engine engaged, speculation began as to whether we would find a birth in the small L-shaped harbour. There were other harbours, but they are larger and tend to be filled with large power boats. We were looking to find our own kind and for a not to eventuate quiet evening.

Just as it seemed we were out of luck, Lamberto spotted a potential birth. It was perhaps two and a half metres wider than Ingeborg's beam; a tight fit. But, Lamberto knows the geometry of Ingeborg and has secured many a different boat in an uncountable number of harbours on the Mediterranean, North Africa coast and the Baltic.

[Image: Ingeborg sits snugly between the motor launch and the other sailing vessels on the left. Her small stature can be observed by comparing mast heights.]

We were met on the land side of the harbour by a man who offered to assist us in securing Ingeborg to the harbour wall. I threw a line at, rather than to, him. Following the securing of the vessel, Lamberto informed me that I needed to learn how to throw a rope. "I would be pleased to learn."

With Ingeborg secured, the harbor's "automated office" visited, payment made and the permit fixed to the bow, it was time for a walk.

[Image: the automated harbour office. The two cylindrical vessels are for glass recycling. Behind the wooden fence are a series of large general waste bins. The three doors visible are toilets for each gender and those with physical impairments. The entrance to the harbour, and Ingeborg, are behind the building. To the left can be seen the bottom of the L-shape of the harbour used by vessels of low draft.]

We took off to the east passing some well maintained gardens and elegant houses to find a space in which various long term tents were erected and Swedish families were enjoying a late summer holiday.

[Image: some of the houses and gardens.]

We passed a heavy concrete type of fortification constructed during the Cold War.

[Image: the foreshore on our walk. At the bottom is a heavy concrete construction from the Cold War.]

There were some sweet blackberries on offer growing by the foreshore. Next to a bush of flowers was an old cast iron type water pump. Lamberto commented that he wanted one of these. It was a pleasure to exercise our legs after the short voyage to Ven.

[Image: Lamberto stands beside his desired water pump, surrounded by pretty summer flowers.]

Upon return to the harbour, a tour of it was undertaken, to observe vessels and facilities. The cost for one evening's stay was approximately 40 USD, which seemed a little extreme. However, the toilet facilities were clean, and the waste disposal was in order.

[Image: Norreborg harbour nestled below the escarpment above, which I would explore the next day. Note the large white “rock” at the end of the breakwater wall to help sailors find the Norreborg harbour, its advertising.]

The harbour would secure Ingeborg against all but the most extreme weather, and harbours require maintenance as do vessels. It was during the little tour that a theme of the evening's discussions emerged, the difference between sailors who race, and mariners. Returning to Ingeborg we shared a beer as the long summer dusk began to fall.

[Image: the “rock” at the end of the breakwater wall.]

A New Type of Gypsie

Lamberto had spent many years of his youth "hanging out" with men of the sea. He delivered many a new yacht, commonly "Bavarias", sailing them a few hunderd nautical miles to be delivered to wealthy people who generally knew far less about boats than he, even as a young man. However, before discussion could really get moving, there was a meal to prepare.

Lamberto was both my skipper and cook. He takes cooking seriously, but at a very practical level. "The Italian kitchen is simple", he would declare. At most four ingredients are to be mixed (ignoring essential basics like salt, pepper, garlic, herbs, olive oil and chill in whatever arangement best suits the dish). What matters is the quality of the ingredients. For our nourishment and enjoyment was, quite unsurpisingly, a pasta. Ingredients two, three and four were augbergine, passata and an italian cheese. It was the manner in which the meal was to be cooked which was the next topic; a pressure coooker.

Lamberto remarked on the value of a pressure cooker aboard a boat. Not only is the meal cooked quickly, which can be of value, but also uses less resources, especially those of fresh water and fuel.

As with cooking any pasta, timing is essential. The pasta and sauce with gated cheese atop was served at 120 degrees centigrade. This, in itself, along with a bottle of Italian red wine greased the conversation as we ate slowly allowing the dish to cool. We returned to the topic of sailors versus mariners during which a rather poetic term emerged.

There were stories of the earliest sailors to race solo around the globe. These were couched in Lamberto's experience with "men of the sea" at the harbours in which he spent many months, years in total, as a young man. They were an itinerant community who respected each others skills and shared their stories and largess. Some wealthy but poorly trained "yachtie" would snag his anchor on rocks in or around a harbor. A nice fee could be charged to dive and free such a snagged anchor, and Lamberto or others would share this simple dividend. Instead of living off the cheap, to be discarded but still very good meats from a butcher, they could invest in more specialist produce. The food would flow aboard someone's vessel as the community enjoyed each others' company. The term was "Gypsies of the Ocean".

Light was beginning to fall, and there was a lesson to be held.

[Image: dusk begin viewed from Ingeborg’s cockpit.]

But, there had been a snag earlier; there was work to be done. The circuit which runs Ingeborg's external lights had developed a short, as demonstrated on the power board. This was the correct time of day to fix and test that. The initial problem had occurred a few days earlier, but the temporary fix was ... temporary. Armed with nail scissors and strong electrical tape, Lamberto exposed the previous work, identified and removed the oxidized sections of wire, and reinsulated and rebound the three wires. "Please go ashore", "yes, skipper". "Can you see the mast light?" "Yes, white, mid mast". "The masthead?" "White". "The bow?" "Red, green, port, starboard." "Good."

During the pleasure of the sailing we had also been testing the sails and their rigging. The test was not for speed or “tweaking” but operability. Before our departure, and now at birth Lamberto was maintaining Ingeborg. In the earlier related article I had commented that a skipper’s responsibility is to the safety of the crew and vessel (without which the crew are in peril). Included with the joy I was experiencing was this focus by my skipper: attention to the vessel and improving the skill of the crew. These work hand-in-hand. The boat must be in good working order, and the better trained the crew, the less risk there is in cases of emergency, or of an emergency occurring.

Following the lights test, Lamberto joined me ashore equipped with a 10 odd meter length of rope of a nice weight, not a 6mm thickness line, but 12mm. Not too light, and not too heavy. My skipper, cook and teacher demonstrated the throwing of a line. I saw the line thrown and unfurl to an almost straight line as gravity brought it to earth.

[Added 2022-10-18]

In “On Seamanship and Seafaring” by Sir Robin Knox-Johnson [ISBN: 978-1-912177-14-1] , leant to me by Lamberto, Robin provides a section on the throwing of ropes (page 57, Throwing a Heaving Line):

Judging from examples I have witnessed recently, the art of throwing a heaving line (or any line come to that) is in danger of being forgotten. All too often you see a line thrown from a boat that failes to reach the intended recipient, although there was planty of line cover the distance. When you see the line tankgel within a metre of the throwser’s arm you know the line was not prepared properly.

This is not just frustrating, it is embarrassing to the thrower. Worse, the failure to get a line ashore might force a boat to make another approach or could cause difficulties if a strong wind in clovwing the bows off a pontoon or wharf. And althrough a heaving line is just a messenger to increase the range you can sent a line, it becomes essential when you are trying to transfer a towline of painter to or from another boat of liferaft.

My skipper was addressing this danger of the art of throwing being forgotten.

[End of addition]

Throwing Ropes

Firstly, the line should be coiled and free of any knot, tangle or other impediment. This, recall, is how cordage is meant to be stowed.

One places the looped rope in one's non-preferred hand. One gently clasps the end of the rope which one shall retain between one's thumb and forefinger of that hand, or better fastens it to the vessel. Across the other three fingers the coils of the rope are supported but not grasped. In the preferred hand one takes a few loops of the rope to form into smaller coils. A coiled rope has loops of roughly 40 cm of depth. These smaller coils which one forms in one's preferred, or throwing hand, should be about half of that. There should be maybe 6 to 8 loops to be thrown. The purpose here is to have some weight to throw. One throws the smaller coil collection together, towards the target. Its weight pulls the larger loops from the open fingers of the other hand. The gentle thumb and forefinger hold retain your end of the line.

Why go to such lengths to "just to throw a rope"? There are many reasons, the foremost of which comports with many elements of learning about the sea. Conditions are not always a calm summer afternoon in a friendly harbour with help at hand. Imagine it is night, raining, with a 20 knot breeze, a 3 metre swell and you have a "man overboard". They have reached the deployed life bouyancy device (and flag). The water is 6 degrees centigrade. You have only a few minutes before hypothermia begins. They need that rope and they need it on the first throw.

On a less dramatic but also mildly important level, one wishes to welcome the assistance of a person ashore by demonstrating that one knows what one is doing.

My first throw, having seen the demonstration, was effective, but poor. I needed a target. Lamberto stood afar as I prepared the line. It went straight to him, with me retaining my end. "Very good", was my reward. "I would like to do that again", was my request. We did. Same result. "Thanks, Lamberto". There was still a half a bottle of italian red awaiting us aboard Ingeborg.

Work had been done, it was time for more stories.

[Image: other travellers take a walk over the breakwater wall.]

All good stories can be told again and again, with each telling being slightly different. This story is both dramatic and extremely important. Thus, its retelling is always welcome. Its begins a few hundred nautical miles off the coast of Morocco, to the northwest of northwestern Africa. For several weeks, maybe a few months, Lamberto has been sailing with Petra, a beautiful and determined Swedish woman. Against gaffaws and a little laughter, Lamberto had declared months earlier to his Gypsies of the Ocean that this woman would be the mother of his children.

To assess the steadfastness of many of his earlier partners, they had been invited aboard Lamberto's vessel of the time. In sequence, after a few days, they would request to be delivered to a harbour for whatever reasons they gave. On this occasion, aboard a catamaran, was the prize Lamberto wished. Their journey, laughter and fishing had taken them from the west coast of Spain to the north coast of Africa and into the Atlantic. There, their well equipped catamaran met a hurricane.

Windsurfing, fore and aft

The old "tall ships" or square rigged vessels are transported with the wind behind them. They "catch" the wind. It pushes them. For "fore and aft" rigged vessels, this same approach is used when "running" before the breeze. The advantages of the fore and aft sail are many but a primary one is that they can move forward into the wind. For this a different force described by Bernoullie's Principle is at play.

As the wind is split between the inner and outer surface of a sail by its leading or windward edge, the luff, the air is forced to take different paths. The outer or leeward path is a tiny degree longer. While the flow across the sails is lamilar, meaning that turbulence is non-existant or minimal, this creates a lower pressure zone on the outer edge of the sail. The same principle is used for aeroplane wings, with the longer edge being on the top, to create the low pressure zone there, which lifts the areoplane. On a sail, the leeward low pressure zone creates a vector of force with a forward component.

In dangerous or difficult conditions, this windward sailing is far less risky that running before the breeze. When running in heavy seas one can bury the bow in a wave causing a complete loss of equilibrium between the forces working on the sails and those on the underwater, hydrodynamic surfaces of the boat. This is a technical way of saying that the stern of the boat gets lifted out of the water, the mainsail may gybe, people are thrown overboard or the boat is layed horizontal on the water with the cabin receiving flooding. These risks are greatly minimized by windward sailing. The key principle for sailing in either direction is that that area of sail aloft is correct for the wind speed: more wind, less sail area.

Sadly, things are a little more complex for a catamaran than a keeled monohull. In heavy conditions it is to be sailed more like a windsurfer than a yacht. This was the problem which Lamberto was addressing during the three day long battle with the hurricane.

As skies darkened, winds rose and the swell morphed into waves reaching 6 m, sail area was reduced to the absolute minimum to maintain a balance. The vessel's mast had a depth to it such that it in itself acted as a small sail. On the foredeck the smallest sail, a storm jib was set. The two combined gave some balance and the all important "way". Way is when the aero and hydrodynamic forces applied to a vessel have some balance and the vessel's rudder, or rudders in the case of a catamaran, is or are able to direct the boat.

The first phase of the hurricane battle was arduous but manageable. The catamaran is "windsurfed" up and across the waves which dwarf the boat. Atop the crest in the white water, way is abandoned and the catamaran is just blown sideways. But, the white water is less dense, her hulls could slip across it as the wave rolls underneath. As she drops down the "back" of the wave, way is regained into the trough. There almost no wind is available and she is lifted upon the new wave, wind builds, way is regained and the windsurfing begins again. Wave after wave after wave.

Poor Petra has quite understandably become very sea sick. See the previous article for learning the colour of bile. That was nothing compared to this. Lamberto reported that he kept a supply of jars of baby food aboard. This is pureed to be as easily digestible as possible, for infants. This Petra was advised to consume so that what little of it could be absorbed by her digestive organs was.

[Image: the colours of dusk.]

Petra's distress did not relieve her of an essential role. She was the navigator. Her task was to mark the vessel's position on charts when opportunity to place a mark became known. Despite all of her distress, she never vomitted on a precious chart.

Eventually, the eye of the hurricane met them. This is not relief. There is no wind. Thus, there is no way. Waves are coming from every direction. They are compounding at cross purposes. The battered boat and crew must continue.

At some point, Lamberto takes what little rest he can in one of the two hulls. Never again would he choose this. The torment being applied to the boat screamed into his ears. Constant loud noises like the breaking of plastic under tension. The boom of a wave hitting the hull. No more. Lamberto's future minimal rest would be taken above, with his body roped to shackles fixed to the deck.

By the third day, the eye had passed. Heavy winds blew again. The burden of tiredness and for Petra, dehydration too, weighed on the two crew. The Moroccan coast was now not too far. Against all odds the catamaran had held. A harbour needed be found. According to the Admiralty charts laid more than a century ago there was one, 50 odd nautical miles distant. Towards the shelter of this potential harbour they steered.

An unexpected nightmare loomed above them as they approached the continental shoreline. The 6 metre waves created by the hurricane were bouncing back off it. These would overlap with the waves driving towards the shore creating 12 m high waves, towering over the vessel. Completely exhausted, this called for desperate measures. A beach could be seen. The "as little risk as possible" plan was to take to the beach. To gain as much speed as possible. Raise the dagger boards at the last minute. Drive the multi-hull onto the sand, survive, and deal with the aftermath after the storm had passed.

Shortly thereafter, Petra asks "what is that light?"

The beaching plan was born from their lack of ability to find the harbour on the charts they had. Soon after sighting, a second light became visible. They were the bow and stern lights of a large cargo vessel. An immediate change of plan is made. Cargo vessel captains know these waters, are well armed with information and will have chosen the safest location to withstand the weather. To them was the new course.

Finally, in the company of these large vessels the harbour was sighted. There was a final scare the day following as Petra became temporarily blind. But, that is another story.

A few days later, Petra asked her mate "could we go to Brazil?"

Finally, the steadfastness that Lamberto needed had been found.

Raucous Danes

There is a happy weariness which comes from boating. The constant roll of the vessel, the wind on one's face and the polarized light reflected off the water create a pleasant tiredness.

[Image: last tasks before bed.]

By 22:00 Lamberto and I had retired to our places. We were rudely kept awake by a conglomeration of Danes starboard of our birth.

The sense of self entitlement, or lack of understanding of community was our early morning discussion. I did, however, enjoy the harbour's watery soundscape after 4 am. Quiet had mostly descended. There was a problem, though.

I could hear a sound which spoke of water leaking into or out of something. But, my skipper was not alarmed. The sound would not recede, and sometime before 6 am an investigation needed be made. Against the harbour wall, just before my forward compartment was a ladder. Some of its steps were hollow and the rising tide was flowing into and out of those tubes creating the sound. Relieved in understanding, I managed an additional hour's sleep before full light called us to the day.

A Morning Walk

Lamberto took to reading a book on an early 20th century tall ship trading mission from Europe to Australia. I took to the escarpment sitting over the harbour and foreshore to the west. The vista atop the escarpment was of wide fields of ripe barley or wheat, with ears curled down and some sections of the fields already reaped.

[Image: a pleasant morning’s walk atop the escarpment.]

On the return trip, one could spy the little harbour between a gap in the trees.

When I returned, Lamberto's book was downed and his morning task of fixing a better single rail track for the starboard block for the headsail was almost complete. Before long, we were again under way, leaving the little harbour behind us.

Fishes and Fishing

The sails were raised and we calmly cruised at 2.5 knots before arriving at a hole in the wind. Not too far away were some large and small fishing vessels.

Lamberto loves fish, and fishing, particularly spear fishing, and cooking and eating fish. We downed sails, and from here the engine would be used. Lamberto's love of fish was expressed as he detailed several modern industrial activities which damage marine ecologies, bottom trawling and fish farming. These, of course, anger him. Bottom trawling litterally destroys the ecosystem on the sea floor. Fish farming includes using antibiotics which encourages antibiotic resistant threats to the wider ecosystem. Fish farming also includes growth hormones which we, and our children, eat, along with the antibiotics. I was most happy, as the engine rhythmicly rumbled below, to give an ear to my skippers annoyance with these self defeating practices. There are other things besides knots which one can learn.

A sequence of four potential fishing locations were visited, with two different rods and lures being employed for the different types of fish expected. A minor effort was made among the fishing vessels. But, they seemed not to be having much success. Then, two wreck locations were sought were we also had no success. Finally, the special location, which shall remain unnamed, was tried to yeild a complete sequence of lack of luck. Were our spirits damaged by this? Not in the slightest!

[Image: one rod with a lure for mackrel.]

We returned to Helsingør. We crossed the ferry lanes, passed Kronborg and slipped into the marina in the early afternoon.

[Image: Helsingør from the southwest. Kronborg can be seen on the right, with the town’s cathedral’s spire on the left. The disturbed water below is evidence of the large ferry around whose stern we had just passed.]

Maintenance and improvements to Ingeborg had been performed and tested. I had received a few good lessons. There had been laughter, plenty of attentive conversation, a few well told stories and not a harsh word spoken.

It was a joyous cruise aboard Ingeborg with Skipper Azzi.

[Image: back at the marina.]

Sources

All images are by the author taken during the cruise, with the exception of the chart.

If you like what you read here, you can please the author by sharing it.

Copyright

This work is copyright 2022 to the blog's author. Any re-publishing or re-use of any part requires express written permission. Use the Comments section to contact the author.