A Lasting Voice to Parliament: A Constitutional Legal Analysis

Australia's upcoming 2023 constitutional referendum

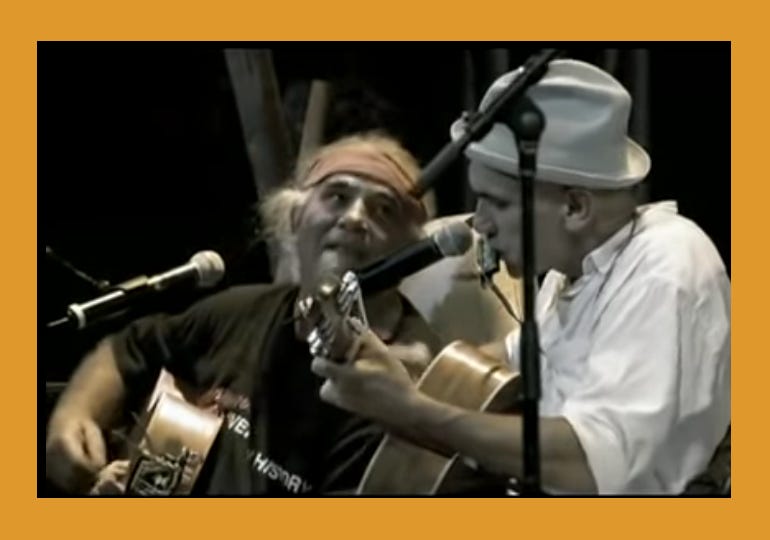

[A frame from the culture section video of Kev Carmody and Paul Kelly singing “From Little Things Big Things Grow”.]

Published: 2023-09-20

Updated 2023-09-23: edited the preamble to replace the adjective indigenous with original or first.

Preface

This is the first of threee articles on the Australian 2023 constitutional referendum. The other two articles cover the No and Yes cases.

Preamble

During the Age of Exploration, perhaps better titled the Age of Colonization, European nation states installed colonial administrations for territories already occupied for tens of thousands of years. With them they brought not only their form of government and its legal instrumentation. They carried with them a sense of advancement and entitlement.

Recent writings on the development of science and technology strive to break the commonly accepted notion of a European dominance of its history. Central American societies developed calendars at least as advanced as their European counterparts by around 1000 CE. The civilizations of the Indian sub-continent developed the critically important understanding of the significance of the number 0. The almighty scientific revolution brought about by the printing press in Europe would not have been possible without the paper invented in China. In North America and Australia, at least, the indigenous peoples developed an deep recognition of their place on and with the lands, rivers and seas and their flora and fauna with which they lived and co-habited. This advanced understanding of ecology occurred before the relatively recent scientific interest in it. While neither developed writing they used story, song and dance to preserve their cultural knowledge.

Jared Diamond's exploration of "Yali's question", why did the European colonizers have so much 'cargo', in "Guns, Germs and Steel" provides a fascinating window into the role that geography, the structure of our planet and its weather patterns, has had on the developments of civilizations and technology. The Eurasian landmass is unique in its possession of extensive fertile lands within a wide latitude with many mighty rivers and the widest collection of domesticateable animals and farmable plants. Trade routes between these fertile river valleys and plains facilitated the exchange of these crops and animals, and the latter for both food and labour. These enabled denser living and city states.

A type of fate was to be visited upon sub-Saharan Africa, the Americas and Australasia when the colonists arrived with their pathogens and weaponry.

That fate can be examined through the lens of the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide [CPPCG]. One cannot retroactively charge persons with crimes before a statue exists as they had no way to know that they may be committing the crime. I mention this legal principle for the majority of this article focuses on legal and constitutional issues.

The CPPCG lists five crimes, any one of which is genocide. The policies and behaviors of European colonial administrations in various parts of the world amount to genocide committed upon the local original peoples, the initial immigrants. On the continent of Australia, British colonial administrations committed all of these crimes, a universal genocide. The multi-generational trauma this caused for the original peoples of Australia remains with them. The trauma of having been involved in these universal genocides also sits in the histories of the later colonists.

The original peoples of Australia resisted the European colonization. Their attempts to engage with the British colonial states and then the independent Commonwealth of Australia and its States are well documented. Those attempts have been repeatedly denied by governments. At least one government institution to facilitate political engagement, ATSIC, was created and then destroyed. Still, Australian indigenous peoples struggle for lasting political engagement with the foreign government which was created to administer the lands of their ancestors without their consultation.

Recognition of the humanity, cultural richness and knowledge of first peoples has been made worldwide. The upcoming constitutional referendum in Australia is a carefully, well crafted opportunity for the electorate to continue this process.

Introduction

On October 14th, 2023, Australian citizens will have their first opportunity since 1999 to participate in a vote which could alter their nation's constitution. This article provides a collection of resources and an overview of the legal consequences for the current and future Australian governments should the vote be passed. Should Australians reject the proposal, it will be added to the long list of rejected proposals for constitutional change which document the history of their direct involvement in their democracy. A No vote will add no responsibility, burden, nor honor to Australia's parliamentarians or government. Should the proposal pass the "double majority" test for Australian constitutional change the legal onus which will be added to parliamentarians is effectively nil. To the government of the day, they will have another lobby group to which they can choose to listen. To the public service they will need to maintain a register and provide the level of support to a body to be created entirely according to legislation passed by the government.

If one does not engage with Australian political media, one may have missed all of the hullabaloo of the discussion of 'Voice To Parliament'. Its all there in Australia's vibrant political and social media, both commercial and government supported.

The term "The Voice" can be misleading to those unfamiliar with the political background to this moment in Australian history. That which is being requested is another voice to be heard by Australian policy makers, one that comes from and represents the collective expression of indigenous Australians. The initiative comes from the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart which was the result of a continent wide, indigenous lead consultation among indigenous peoples. A poor analysis takes the definite article "The" in the "The Voice" and supposes that this will replace other voices. The Voice is representative of the lasting engagement which indigenous Australians have been organizing and protesting towards since the Commonwealth's founding.

[Uluru]

As mentioned above, previous government bodies have come and gone to serve as advisory bodies to the federal governments since the 1967 referendum enabled the Australian parliament to legislate for indigenous Australians. Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islanders are asking for a lasting voice to parliament, a lasting mechanism to inform government policy of their considerations. A constitutionally enshrined body is the natural, legal mechanism to realize this.

The opportunity to create this enduring channel of communication between Australia's legislative and executive arms of government and a representation of Australia's indigenous peoples rests with the Australian electorate.

Australia's Constitution and Referenda

Australia's constitution [full, shorter reference] was born with the Commonwealth of Australia on January 1st 1901 following the passing of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act by the United Kingdom's parliament. During the preceding two decades the text of the document was developed in Australia among the 6 independent British colonial States of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia which had been established on the Australian continent.

The constitution describes the bicameral parliament and some other government structures, along with responsibilities, as one would expect. It provides one, and only one, mechanism for its alteration, a constitutional referendum, which is formally described in Chapter 8. A bill is to pass both houses of the Australian parliament which describes how the constitution is to be altered. Notification of the existence of the bill agreed by the parliament, and the agreed wording to be used in the referendum's voting question are to be published to alert the citizenry to the role they shall play in deciding the vote. (Technically, the constitution is less prescriptive. The Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 describes the process used.)

Australian citizens are required to vote. A fine can be issued for failure to turn up and have one's participation registered by the Australian Electoral Commission who administer federal elections.

Some Australians have a larrikin streak. Over the years they have developed a whole variety of ways with which to protest either the requirement to vote or that they are disappointed with the choices available. A classic, used in electoral votes, is to vote "informal" by numbering the, for example 4, candidates: 3,5,2,4, or 5, 5, 5, 5. One could screw the ballot up in disgust and place it in a waste bin, or calmly deposit a pristine ballot in the return box. The Australian Electoral Commission takes all of this in its sway. Turning up and being recorded as having received a ballot is participation. What one does after that is personal choice, though displaying disrespect for the public servants who run the elections is neither productive nor humorous.

Referenda have been created and run at all levels of Australian government, including that of Local Councils since the modern nation's creation. Interestingly, their frequency has fallen away over the last 50 years. All manner of things have turned up, like whether to close local swimming pools in a council area (very unlikely to succeed) or when the closing hour should be for Public Houses (bars). [See the reference in Sources for an interesting podcast on the history of referenda in Australia.]

A referendum is an effective method for a governing political party to hand off a political "hot potato" to the electorate. A referendum is essentially an instance of direct democracy where the voting population decides a matter rather than their representatives, though the representatives get to choose the question and when it is to be voted upon. A constitutional referendum is obviously federal and must be executed in accordance with the provisions outlined in Chapter 8 of the constitution, one of which is the requirement for a proposal's passing, known as the "double majority".

A majority (half plus one if the number is even) of national voters and a majority of States are required to approve a constitutional referendum. Because Australia has six states, this means a referendum must be passed in four states. This heavy burden has resulted in only 8 of the 44 constitutional referenda in Australia's history being passed. 5 of the 44 have failed the State majority while achieving the popular majority. The remaining 31 have failed to achieve a majority of voters which indicates how resistant to changing the constitution Australian voters have been.

For the first 76 years of Australia's history residents of its two territories, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory, could not vote in federal referenda. In 1977, this strange aberration was fixed by both improving the situation and making it stranger still. Territorians are since required to vote in referenda. Their votes count towards the national total, but have no bearing on any State total. As an Australian, this author is rather proud of this unwieldy application of Australia's universal suffrage.

Each of the 44 historical, constitutional referenda can yield a yarn to entertain a gathering, whether around a suburban dinner table or a fire out in "the bush". A few are given brief mention below to provide framing for the upcoming, latest instance.

67-Yes and 06-Yes with a nod to 67-No

Due to the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1962, which was the government response to the House of Representatives Select Committee on Voting Rights of Aborigines (established in April 1961), indigenous people were given the option to enroll to vote. Five years later in 1967, two constitutional referenda were put to the citizenry on a single ballot.

As a quick statistical aside, all but two constitutional referendum ballots contained multiple referenda questions. The prize goes to the 1913 ballot which had six. Two or four questions on a ballot are common. The outlier singular ballots are the first and the one about to occur. The co-location of questions on a ballot is due to the geography of Australia. The nation is big, very big, the only continent encompassed by a single nation and only exceeded in size by the five largest nations (Russia, the USA, China, Canada and Brazil). The first ballot, 06-Yes (from 1906), corrected a cock-up by the early colonialists and their British erstwhile overlords. The constitution required that elections for the House of Representatives (the 'lower' house) and Senate occur 6 months distant from each other. This was just stupid and required fixing. Holding a federal election is cumbersome on a continent. The constitutional change to hold these elections at the same time was carried by all states and 82.5% of the voting population.

On the 1967 dual referenda ballot, one was an attempt by the House of Representatives to increase its size independently of a corresponding increase in Senate numbers as stipulated in the constitution. The constitutional requirement is that the representative to senator ratio is two to one, such that at a joint sitting the senators comprise a third of the combined number. Australia's citizenry didn't like the look of this slimy move by the reps to dominate combined sittings. The only state which carried this, and narrowly at that, was the most populous, New South Wales. The little states (in terms of population) of Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia rather like their outsized senatorial influence and so the proposal was pretty much doomed at the outset.

It is the second question from the 1967 ballot which directly concerns the upcoming 2023 ballot. The powers of the Australian legislature (the parliament, which is comprised of both houses) are detailed in Section 51, a part of Chapter 5, aptly titled "Powers of the Parliament". There are 39 clauses describing these powers, one of which has a sub-clause and all of which legally include the preamble, which reads:

The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to:

Clause xxvi (26) was to have two commas and eight words removed from it. At the time of the vote, and since the document came into effect, it read:

(xxvi) the people of any race, other than the aboriginal race in any State, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws;

The amended constitution with the eight words and two commas removed reads:

(xxvi) the people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws;

Please pay particular attention to what this clause used to say. The federal government can make special laws deemed necessary for the people of any race (for the peace, order and good government of the Commonwealth) except for the aboriginal race for whom no such special laws are permitted by the federal parliament. This is a continuation of the pre-federal period in which laws pertaining to the indigenous population were enacted in the (British colonial) State parliaments.

I'm not a lawyer, much less an Australian constitutional lawyer, but I think the above re-expression of the state of affairs before the 67-Yes vote took effect is pretty close to the mark. This constitutional clause forbade the Australian national parliament from legislating on behalf of the native peoples of Australia, and this had been the state of affairs for in excess of 65 years.

The Australians of 1967 were having none of that, thank you very much. Waddaya mean we can't make laws for some of the people who live in this country, and for that matter, have been able to vote for 5 years and whose ancestors have been living here since before we got here! We smell colonial jiggery-pockery racism!

Please excuse me as I labour this point, for I believe it may have been overlooked by some in their analysis of the upcoming referendum. There is one blinding reason why the 'Constitution Alteration (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice) 2023' [PDF] bill was able to pass both houses of the Australian parliament. This bill, which creates the about to occur constitutional referendum, would have been unconstitutional without the 67-Yes vote. The vast majority of Australia's voting population have both of their parents, or all of their grandparents or possibly themselves to thank for this. So outstanding was Australia's response to this constitutional referendum that it even beat fixing the colonial stupidity in the 06-Yes referendum which was carried by 82.5%.

The 67-Yes is the only referendum to register more than a 90% Yes vote. This is the closest thing Australia has seen to unanimity in a constitutional referendum. Without it, the 2023 question would seem constitutionally impossible.

Another way to view the two is that the 2023 question is a natural, political development of the 67-Yes vote.

[Australia’s Parliament building in the capital, Canberra.]

The Constitutional Question for 2023

The referendum question will be a Yes or No response to:

A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognize the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

Do you approve this proposed alteration?

The "A Proposed Law" is the bill named and linked above. It is trivially short and could not possibly be misunderstood, instructing that the following words are to be inserted after the current last chapter (8) of the constitution:

Chapter IX — Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

129 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice

In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

(i) there shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

(ii) the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

(iii) the Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

Professor Emerita Anne Twomey, University of Sydney, also the director of the Constitutional Reform Unit, is regarded as one of Australia's most eminent constitutional legal scholars. She along with other Australian constitutional experts were consulted by parliament to craft the constitutional text for the bill. On March 26th, 2023 an article by Professor Twomey subtitled “We now know exactly what question the Voice referendum will ask Australians” was published in Australian Geographic. It presented the final wording used in the bill and thus to be potentially added to the constitution. The article also described the reasons why some adjustments were made to the draft constitutional text and why other phrases which were discussed remained unchanged.

For example, the phrase "First Peoples" is used to avoid the more political phrase "First Nations". It also avoids any confusion which may be injected into political debate about the referendum which hangs on the use of the word "nation".

In the "nothing needs be changed" area the use of "Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islanders" an accepted phrase to refer to the many diverse groups who constitute the original peoples of the lands and waters now under the jurisdiction of the Commonwealth of Australia. It has been used in existing legislation, for example the short lived advisory body mentioned earlier, ATSIC.

Twomey's article is unsurprisingly concise. From it one can understand the care and clarity contained in the words and phrases which may be added to the Commonwealth of Australia's constitution. Should you be eligable to vote, reading it may assist in understanding the thinking of the constitutional scholars and parliamentarians during their deliberations for crafting the potential constitutional change.

I hope that the above description and references have made clear the mechanism of Australia's constitutional change process, some relevant history, and the care which has been taken by the Australian parliament in creating the upcoming referendum.

Consequences

As indicated in the introduction to this article, the legal consequence of a No result are merely that it shall be added to the other 36 No results by the public service who pride themselves in keeping accurate and reliable records of legal matters relating to Australia's governance. This is no burden, for this will be done anyway, though added to the 8 Yeses should the other result be returned.

Technically, a Yes result requires assent from Australia's head of state, the British monarch, King Charles III. Nobody expects this to be any more than a formality. A Yes result will have some, though very little legal consequence for some branches of the Australian government.

There will be no effect whatsoever on the judicial branch.

The legislative branch will be required, in reasonable time, to pass legislation which establishes the first version of the body named in the bill, the "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice" (which will be instantly acronymed to ATSIV (at-sieve)). Following this, the public service of the executive branch will need to perform the tasks to meet the requirements which are set out in the bill which creates the body. Office space will be allocated, a budget line created, a domain and web-site created, supporting staff will be hired like a secretariat and so on.

Should ATSIV choose to "make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples" it would be remiss of the public service not to record these representations as acknowledgment of receipt. So, this task will fall to them.

And "that's all she wrote".

Nobody is bound to read the representations. Future governments can do whatever they want with ATSIV except destroy it (without another referendum). No other organization has the authority to modify it. None. An Australian government can under-fund, ignore, marginalize, ridicule, or engage and honor ATSIV without legal consequence.

To again labour a point, a Yes result will force the government to create ATSIV, which will become another 'voice' (read "lobby group") among the many which advise or attempt to advise the government of the day on policy. ATSIV is constrained to only make representations to the government "on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples". One may read into this that ATSIV's representations may carry some weight. This would seem the intention, though this, like funding, internal governance and a myriad of other small details, will be entirely up to the government of the day to decide, through the passing of legislation, and nobody else's.

One may ask, so what's all the fuss about?

This topic shall be addressed in further articles.

NB:

The use of monikers like '67-Yes', '06-Yes' and '67-No' are not generally useful to label Australian constitutional referenda. 77-No is okay, but 77-Yes does not disambiguate the three referenda questions passed on that ballot. One would need "77-Yes,Senate Vacancies", for example.

Sources

[below, APH refers to Australia(n) Parliament House, the website published by the public service providing authoritative documents on bills, the constitution and other legal matters]

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, Jared Diamond, Barnes and Noble, first published 1997

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, UN, adopted by General Assembly resolution 260 A (III) on 1948-12-09

Uluru Statement from the Heart, representatives of Australia's indigenous peoples at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, 2017

Uluru Statement: a quick guide, Australian Parliament House, 2017-06-17

VOICE FROM THE PAST: The Real Story Behind The Abolition Of ATSIC, Chris Graham & Brian Johnstone, New Matilda, 2023-09-08

The Australian Constitution, APH

Infosheet 13 - The Constitution, no author, APH, 2019-07

Podcast #102: A history of Australian referendums, Ben Raue with Paul Kildea and Andre Brett, The Tally Room, 2023-09-08

Referendums in Australia, Wikipedia

Indigenous Australians’ right to vote, National Museum of Australia, last updated 2023-05-16

The 1967 Referendum, Matthew Thomas, Parliament of Australia, 2017-05-25

Constitutional referendums in Australia: a quick guide, Dr Damon Muller, APH, updated 2023-05-08

Constitution Alteration (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice) 2023, APH, "As passed by both Houses", APH, 2023

A constitutional law expert explains the Voice referendum question, [Professor] Anne Twomey [director of the Constitutional Reform Unit at the University of Sydney], Australian Geographic, 2023-03-26

Professor Emerita Anne Twomey, University of Sydney

Culture

This had to be the culture section.

From Little Things Big Things Grow - Kev Carmody and Paul Kelly, Kelly, Carmody and band and guests, dm7ify, uploaded 2012-01-25

Comments: on topic, no abuse.

Thanks for this. I look forward to your follow up articles. The most important feature of this proposed amendment is the recognition of Australia’s First People but I have been worrying about what additional burdens or divisions it may bring. From what I’ve seen, the Yes campaign has not been well presented and is now beginning to become moralising and bullying, seemingly carrying the same woke wedge we have been seeing in recent years. So your words are helping me better understand what it’s about.