[Image: The skipper’s left hand feels the rudder as his eyes and mind embrace conditions at his cathedral. The observant may note the black cord on the wheel marking center steering. The yacht is well balanced under a light helm. The minimum of white water astern and the relaxed countenance of the skipper support this inference.]

Publication date: 2022-05-24

Update 2022-05-24: Some corrections and additions: Any uncertainty as to the object struck outside Sydney harbour has been removed. It was a whale. Secondly, “G for George” is a 15 tonne aircraft and is most certainly resting on the floor. The persons in the image of Henry and Archie were mislabeled. They are now correctly identified. It is a family photograph. Additional observation is added to some other image commentary. An anecdote regarding a “Dad special” spinnaker has been added.

Update 2022-05-25: An example of foredeck order and preparedness is provided in a description of the optimal preparation for spinnaker setting. An acknowledgement for the graphical research which supports this article was added.

Acknowledgement:

Most of the original images in this article were provided by the skipper’s wife who herself is an accomplished skipper.

A Characterization of the Man

My father's method of simplifying sports codes is to collectively identify them by equipment. Rugby Union, Soccer and Football are all variations of "ball". Tennis, Hockey, Baseball and Cricket are "ball and stick". Sailing is "rag and stick". This endearing simplification speaks of the man himself.

My father's two sporting passions are rugby and sailing. From a young age he played rugby for his school and sailed dinghies on Sydney harbour. Each sport has lead to a life threatening incident.

Scrummage in rugby creates a rather unique bond. The members of the scrum must work in unison to counter the opposition. The front of a scrum is held together and coordinated by the hooker, whose arms are splayed left and right over the shoulders of the two other members of the front row. My other father (my family story is complex) described this man as the best hooker he's ever played beside. This hooker was so good that his team, Colleagues, won many a title. He was likely to be selected for the New South Wales rugby team. This potential was torn from him during a game.

The ball had been kicked high. My father called "Mark" to signal that he would catch the ball. During a violation of rules he was simultaneously tackled from three sides, left, right and from the front, as he took the catch. The instant stomach rupture almost killed him. No possibility to represent his state in his beloved game would arrive. Instead, he bares the scars of the operation which saved his life.

Sailing with a friend Dr. Michael Kay outside of Sydney harbour, my father’s yacht struck a whale, cracking its hull. For hours the two man crew struggled to contain the breach and bail sea water to keep the vessel afloat as they battled to return to harbour. They were exhausted at the point of reaching their birth in Rose Bay. The vessel's gunnels were under the waterline. Relieved, as they stood on solid ground, the yacht sank behind them.

Away from the fields or seas of sports, my father's other love is for dogs, their companionship and personality. With the blessing of his second wife they have two vibrant daughters. His love for them all has not diminished his affection for dogs. He has remarked that he needed male dogs in the house to balance estrogen levels. My earliest memories involve the house in which we lived, and Nino, my father's faithful companion. One could easily measure this man's life by the dog, or dogs which were such an integral part of his, and his family's, life. Nino. Henry and Archie. Jones. The list continues, including the recent Miles, Noodle and Bogart.

[Image: Beginning with the left of the two images, my father’s brother (left), he (center) and his deceased mother Alice (right) comfort two dogs being clipped. Henry (left) and Archie (right) were Old English Sheepdogs. The image is taken at Roslyn Gardens, Elizabeth Bay, circa 1982. Henry, the first of the litter, and Archie, the runt, were born at the lighthouse which illuminates Seal Rocks. The image to the right shows my father’s youngest daughter astride Archie, the most joyous of the two dogs. This image is taken in the suburb of Seaforth, in the 1990’s. Seal Rocks are visually highlighted at the conclusion of this article. The painted work there is by the daughter riding Archie.]

Pulling Ropes

As a child I sailed on Sydney Harbour aboard Tangara, a 27 foot old yacht. Following salvage after her adventure with the whale, my father acquired a mooring for Tangara off the shorefront of his elder brother’s house by the Neutral Bay ferry wharf. While my father's relationship with dogs complimented his life with compassion, his boat was his cathedral. With his hand on the tiller and a nor'easter blowing through his hair he eased life’s stresses. He communed with friends and the elements. I had no understanding whatsoever of the mechanics of the yacht, though I was well educated of it dangers. "Pull that rope." "Yes, Dad."

This would change when, as a young man, I learned with and was challenged by my father. I recall the exact moment when the idea formed. We were on a southerly reach toward Shark Island in Port Jackson. Our fractionally rigged boat invested its power in the mainsail. I had the mainsail’s sheet in hand. ("Sheet" is a nautical term for a rope attached to a fore and aft sail's free corner, its clew). A gust blew and the vessel began to heel. Easing the sheet, I felt the power of the sail surge through our boat as she regained her balance. There was beauty in that moment. With the eased sheet the mainsail flexed and the gust rolled from it's centre as our yacht righted herself. In the moment I understood the relationship between sail and steering. I was beginning to feel a yacht. My father stood behind me, hands on the helm, as I began to recognize the required unison of our roles.

We were sailing with friends on a pleasant Friday afternoon for a race around the harbour. This was a "no extras" race, meaning that no spinnaker shall be deployed. Soon thereafter I laid the challenge to my father: "Let's do some real racing!" By this I meant 'full' racing, with extras. His response was emblematic. "Ok. Find a crew."

At the time I worked for a company whose main business was with the Hydrographic Office of the Royal Australian Navy. This office is responsible for the publication of accurate charts for all of Australia's territorial waters. Australia’s coastline is immense. The office’s charge is not only the continental and Tasmanian coasts. Included are many islands and the world's longest reef. These charts support Australia’s naval and civilian mariners. The Office’s charts also enable the vast majority of the nation’s international trade.

The required crew were found among my professional colleagues working for Hydrographic Sciences Australia. Two and half years, involving five racing seasons, provided us with a host of adventures.

A Shot Across the Bow

During our first season of competition it became abundantly clear that one of our biggest problems was our foredeck. We were neither setting nor recovering our spinnaker well. The tasked crew member was insufficiently motivated and skilled; it was time for a change of personnel. I accepted the role, and replaced myself on the mainsheet with a most intelligent and reliable man, Scott. He and I diligently studied the book "Advanced Racing Sailing Tactics" provided to us by our skipper. Study of the detailed work proved invaluable.

Often unremarked but of equal import were our studies of our skipper’s yacht, Laissez Faire. Repeatedly I questioned Scott to name all nine lines fixed to the deck, left to right, in order. In moments of emergency one must know where lines are. The mainsail is the most powerful and complex of sails to control and is in constant use. The cockpit position of the mainsheet hand provides access to controls of all halyards and other essential lines. Our mainsheet hand, Scott, was the nerve centre of Laissez Faire.

Among our studies we took the mainsail ashore and laid it out on the green grasses of the Squadron’s foreshore. Batons were replaced and sail tape applied for repair.

My task was to commit to memory every part of the foredeck; all halyards, deck lines, blocks and spars, the correct setting, launching, gybing, retrieval and re-packing of our spinnakers among other procedures.

[Image: Racing on Sydney harbour. Both fully and fractionally rigged yachts are in view, as are differences in sail choice and design. Our family’s later yacht, Enigma, is in the foreground displaying sail number 6322.]

A spectacular moment announced itself during our penultimate Winter Series.

During winter on Sydney harbour a westerly wind may blow. Having rounded our windward mark off Kirribilli, we launched a “Dad special” which he had brought aboard just that morning. This ancient, rust stained, tiny spinnaker was set aloft with a few metres of halyard from mast to its head. The westerly blew and blew harder. To our port and starboard competitors were broaching left and right as we steered dead downwind toward Shark Island under smaller sail. Approaching the leeward mark, the foredeck was in action preparing for spinnaker recovery and coordinating with the cockpit. “Are you ready, Scott?” Then, an almighty boom, like a gunshot, sounded. The head of our spinnaker literally exploded. The body of the sail fell gently around me. Its a perilous lift on a bosun’s chair to the top of a mast to recover a halyard. This is why yachts have two spinnaker halyards. The control and location of the second were well known to Scott, myself and our skipper.

The event served an educational purpose. Repairing the mainsail, laid out on land, had made visible to Scott and myself the size of our dominant sail. The use of blocks and winches hides the power of a sail from the crew in the cockpit. The foredeck is more exposed. This explosion sent an audible message to our crew of the power which were engaged in directing.

Being responsible for the two largest sails we, the mainsheet and foredeck hands, were the engine of our yacht . I can never thank Scott enough for the joy of working with him, and the rest of the crew, during those five campaigns. The application or restraint of this engine were under the command of our pragmatic skipper.

One of the most laughable moments involved my father's old rugby friend, "Ripper". He must have been a rugby player who successfully “ripped” the ball from the breakdown following a successful tackle of the opposition.

Yacht racing bares some semblance to scrummage; it requires effort in unison. Our skipper oversaw our increasingly unified efforts. He allowed us to educate ourselves by experience and error, intervening when our action or inaction, presented risk to the vessel or crew. Under his gentle guidance our crew evolved into an effective team.

The "laughable" event occurred early in my tenure on the foredeck. I had completely failed to "keep things in order". If there is a mantra for the foredeck, it is this: Order. A corollary may be "place things where one next needs them". The foredeck demands foreknowledge.

A instructive example of these demands is the optimal preparation for raising a spinnaker after rounding a windward mark. One does not place the packed spinnaker on the foredeck during the last tack to the mark, but the preceding one. This allows unimpeded access to the rail to fix the bag containing the sail. Thus, one does not disturb air driving the headsail. It is both safer and improves boat performance. As foredeck, one’s window of best opportunity begins following the third last tack towards the mark. That spinnaker should already have been carefully packed: order and foreknowledge.

Our spinnaker was to be taken down, and in so doing I allowed a sheet to wrap itself around my leg. In an instant I am on my back with one bound leg aloft. I call out, "Ease the sheet!" To this my father's friend, Ripper, sheet in hand, replies:

How much is it worth?

Mirth achieved, I was released from my bind. I was appropriately and mercilessly ribbed for my carelessness back on solid ground at the “Yachtsman’s Bar”. From the crew’s perspective the hilarious event impacted our yacht’s performance.

A skipper is responsible for the health of vessel and crew. My inattention had placed our skipper’s responsibilities in jeopardy.

The Value of Charts

Study of the Tactics book was mostly aboard trains to and from the Wollongong headquarters of the Navy's Hydrographic Office. What gift was given by my work for the company which collaborated with the Hydrographic Office? We had the best charts, bar none.

[Image: A photograph of the back of a reprint of Matthew Finders’ work documenting his command of The Investigator’s circumnavigation of the unknown continent of Terra Australis. Captain Cook’s earlier charting prowess requires acknowledgement. A colleague at the company asserted this his charts for some sections of Australia’s eastern coasts remain the most accurate, 250 years later. Aided by determination and a plumb bob and not laser, airborne depth sounders renders Cook’s achievements aboard the Endeavour even more remarkable.]

Charting Courses

When hosting a racing event on Sydney Harbour one shall use its features. A series of courses, both full and shortened, are defined. The course for a day's race is chosen by wind direction such that the first leg is windward. The race committee sets the course, though cannot control the wind. Meteorological wind predictions are used to declare a full or shortened course. A course may be shortened during a race, should conditions change.

One shall keep a weather eye on the committee boat for any change of signal flags.

Our charts contained accurate information on the locations of land and the depth of water. Their value lay over this; the course marks to be rounded, in which order and in which direction, short and full. Just as our foredeck was poor in our first season, so was our preparedness for courses. We were now aided by detailed, laminated, colour highlighted charts of every course. We would not be defeated by confusion.

Another vagary of yacht racing is the scoring system. Whereas most sports work on the basis of "more points wins", racing is the opposite.

Imagine a fleet of 20 registered boats. 18 turn up on the day of race. The winner is awarded one point, with two for second place, etc.. The two boats that did not compete are awarded 21 points (number of competitors plus one). One's aim is to minimize point accrual, and most certainly to start every race.

One morning the race committee’s boat set a start line off Bradley’s Head. To describe conditions as blustery would be a minimization. There were white caps everywhere. Racing is abandoned as dangerous in over 30 knot breezes. During one tack as our skipper repositioned Laissez Faire behind the start line, over a metre of our reefed mainsail’s boom dragged through the water, submerged. Four other boats joined us at the start line. We were deeply frustrated when the committee boat raised flag “N” which signaled “No more racing today”. All we needed was to cross the start line for a 5th place. Though deprived, we were there, demonstrating our commitment.

[Image: the “N”, or call sign “November”, flag which signaled “No more racing today”.]

To add confusion to the points calculation mix, in a mixed fleet, each boat is assigned a handicap. This is multiplied by the boat's elapsed race time to produce "adjusted time". The adjusted time is used to determine placings. Thus, one may be fourth over the finish line and win, if one's handicap is "better" than the earlier three yachts. One's handicap is recalculated after each race. If one wins well, one's handicap may be significantly worsened. As my father would say, a handicapper can beat anyone.

Our fifth competition was the 2000 Winter Series in which Laissez Faire was victorious by the slimmest of margins. Our points were equal lowest with another yacht. The difference was "count back". How many races had we won compared to our level competitor? We won by one extra, previous race victory. Laissez Faire offers condolences to Alouette and thanks her crew, the fleet, and the race committee for the hard fought series.

[Image: Enigma under sail. She is gently heeled and the leeward surface of the mainsail is slightly fouled by her headsail. This conflict between the power of the mainsail and the balance provided by the headsail is a constant challenge for all sloops, particularly those which are fractionally rigged. Working to counter this slight imbalance are Engima’s immersed surfaces; her hull, keel and rudder.]

Watching the Water

Appearances can be misleading. Laissez Faire was racing at the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron. Our skipper always arrived in good time.

He walked through the "Yachtsman's Bar" on his way to the Tender to be ferried to his yacht. Oftentimes, our skipper would be dressed in paint splattered shorts and an aging shirt. However, his shoes were stable, and his hat secure. He strode past the well dressed towards the water, which cares little for one's attire. This contrasts with the award ceremony during which our skipper was impeccably dressed to accept his recognition by a front row of Sydney society. He can scrummage with the best of 'em.

Our skipper is also an avid reader of history. While his studies are global, he has paid particular attention to European conflicts. Antiquity through the Napoleonic Wars, including detailed attention to World War II, have been his historical course.

This last topic is entirely unsurprising; he was born during the conflict. His wife's father was the bombadier aboard "G for George", a Lancaster bomber, which proudly rests in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. I recall as a boy being warned that no flash photographs were to be taken of "Pops" should it trigger recall of the horror he experienced in the European theatre of that world war.

[Screenshot: From the Australian War Memorial’s article on “G for George”, aboard which “Pops” flew. One of his granddaughter’s names echoes that of the aeroplane.]

My uncle, who shares my grandfather's name with my father's grandson, is an accomplished choralist, singing in a choir for the Sydney Opera house. He and his wife, together with my father and his, share cultural ties with Europe, and Italy in particular. The older brother and wife both speak Italian. Our family's ties with Italy are extensive. The small image to the top right of the article is of two statues on a bridge over the Tiber taken during a family visit to Rome. My uncle and his wife may be more able to comprehend my recent skipper's reports on our a voyage around Sjælland, included as a video annex to this article.

[Image: From left to right, my father’s younger brother, himself and his older brother, racing in Port Jackson aboard Laissez Faire.]

Gifts

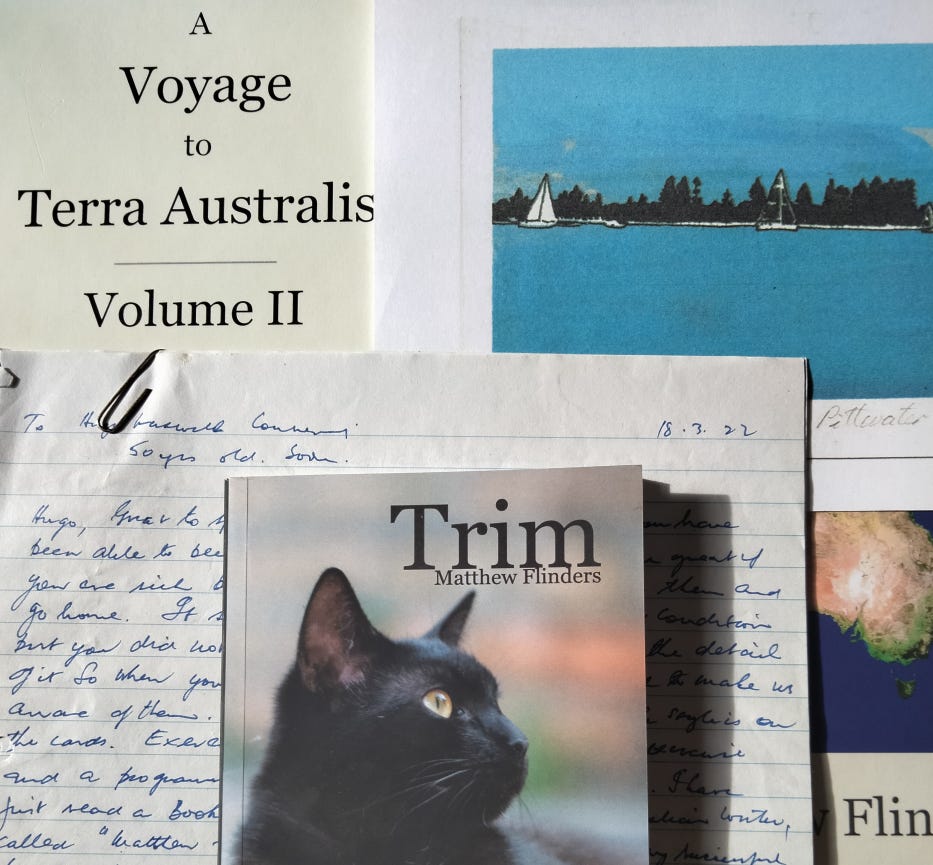

My father and family chose to send me a gift commemorating my 50 orbits of our star.

Preceeding this gift were two paperbacks delivered by commercial services from a book store. The foremost of these two initial books is a dramatisation of Matthew Flinders’ circumnavigation of Terra Australis by Rob Mundle, "Flinders" subtitled "The Man Who Mapped Australia".

Here the rivers of history and seamanship converge.

One should note that the British settlement of Terra Australis began a two century long genocide of the continent's native peoples, and that Commander Flinders' efforts were to further the efficiency of maritime transports to and from the new colony. This increased trade profits, the health of the colony and the continued oppression of the native population.

The arrival of these first two books was merely to whet my appetite. I was informed that my father had written me a letter, by hand, and that this would arrive in time. Sent digital scans of the letter, I declined to view them. I waited for the actual paper. I wanted to feel it in my fingers and allow my aging eyes to struggle to read my father's hand.

Modern technology allowed me to be informed of the package's imminent arrival some two months after the birthday anniversary. It was delivered into my hands by the daughter of a family of friends living down the road. I immediately notified the sender of receipt of the package, but trepidation stayed my want to reveal its contents. An hour later, "Trepidation be damned!" This cat's curiosity could not be contained.

The box had traveled almost half the way around our beautiful and watery world. Violence had been visited upon it during its voyage. Flinders aboard The Investigator could surely have delivered this package with less damage. The time to investigate had arrived. Tender care was employed to open the resolutely taped package.

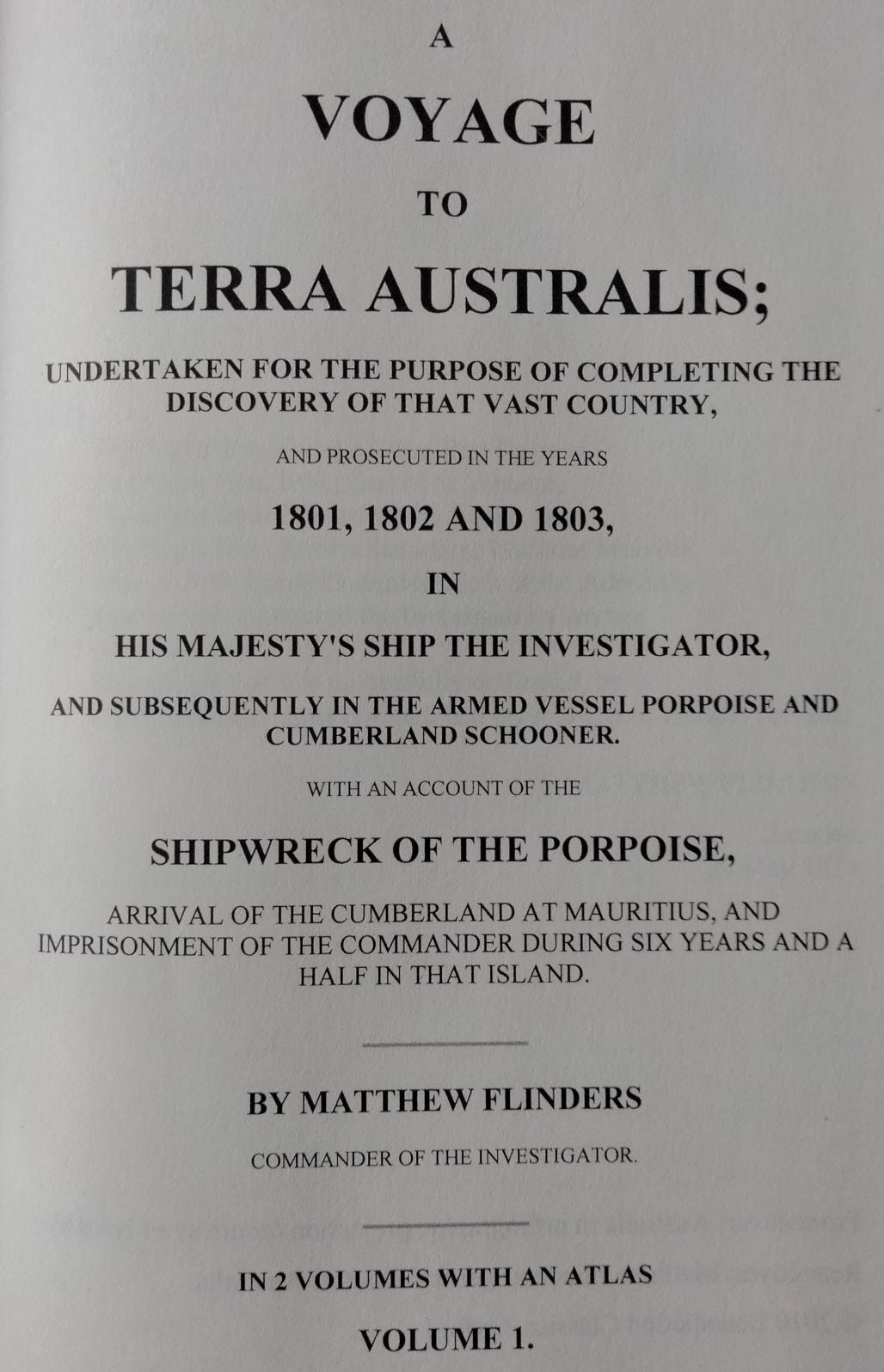

Its heaviest contents were two hard backed books; the two volumes of Commander Matthew Flinders’ account of the circumnavigation of Terra Australis, first published May 20th, 1814.

[Image: The title page of Volume 1 of Flinders’ account of the first circumnavigation and charting of Australia’s coastal waters.]

Flinders' astonishing accomplishment is largely unremarked in Australia's education. The story of Burke and Wills' tragically failed expedition into Australia's central deserts are of more interest. That expedition pales into insignificance compared to Flinders' command of The Investigator's continental circumnavigation and charting.

Trim

Setting these two tomes aside, my tentative hand grasps a smaller book, a monograph written by Flinders as a tribute to his cat, Trim. Flinders' eulogy of his precious companion reads:

To the memory of Trim,

the best and most illustrious of his race,

the most affectionate of friends,

faithful of servants,

and best of creatures.

He made the tour of the globe,

and a voyage to Australia,

which he circumnavigated,

and was ever the delight and plea-

sure of his fellow voyagers.

[...]

Trim was born in the Southern Indian

Ocean, in the year 1799, and perished as

above in the Isle of France in 1804.

Peace be to his shade, and Hon-

our to his memory.

[Image: Our “Trim”, Douzi, receives affection from my father’s granddaughter. While not a seafarer, he was born in Tehran, Iran has lived in Paris, France and Helsingør, Denmark. He is a well traveled cat.]

Working the Sails

A few years ago I received the privilege to join the husband of the family who completed the delivery of this package of gifts, aboard his yacht Ingeborg. We would compete in the Sjælland Rundt (Around Zealand) sailing race. The race begins in Helsingør (Elsinore), this time starting westward, with completion back in Helsingør circumnavigating the island. Together, we laughed and struggled, vomited and rested, celebrated and sailed around Denmark's largest island. My skipper, Lamberto, will proudly tell you that although we sailed the last boat to complete the race, we beat all of the faster multi-hulls on adjusted time.

[Image: my skipper’s toes before calm waters during a northern tack under a solstice northern skyline, on Øresund. The port and starboard bow lights are visible during this dusk and dawn.]

My study of yacht racing, under my father's tutelage, has always focused on the adjustment of sails. This is what I do. Yes, I had joyous moments looking astern to see the multi-coloured lights of mid-summer during this race. Dusk and dawn are merged on the northern Baltic during the solstice at which time the race runs. I looked astern in wonderment with Ingeborg's tiller in hand as my skipper rested. But, my job was to work the sails.

Trim.

[Image: early morning, close to the island of Møn aboard Ingeborg, June 2019.]

Holding this booklet dedicated to Trim brought water to my eyes. Years have I spent guided by my father's patience as I learned the mechanics of Bernouilli's Principle which keeps aeroplanes aloft and sailing vessels working to windward.

The box was not yet empty. A deeper treasure lay within.

Sometimes the small is significant. A paperclip bound the letter. Ragged edges of pages ripped from a spiral bound pad were evident. I was reminded of our skipper greeting his colleagues and competitors on the hardstand of the Yacht Squadron in his dilapidated T-shirt and painted pants. I had Flinders' two century old account, and Trim’s memory staring at me as I held this most precious of hand crafted gifts.

[Image: Gifts arrayed.]

The letter did not come unwrapped. It was folded within a print of painted art, titled "Sailing on Pittwater". Pittwater is the next sound to the north of Port Jackson on both of which our family regularly races. Still further to the north are the beauty and shipping dangers of Seal Rocks, recently painted by my father's youngest daughter. Not in view, atop the headland to the right, is the lighthouse at which Henry and Archie were born. Peace be to their shades.

[Image: A painting of Seal Rocks, by a younger G.]

I have not the language to express the level of tenderness and love contained in this globe traveled, battered package.

With thanks.

[Image: Seal Rocks, water and a most magnificent sky. Composed and captured by the skipper’s wife. Do not be deceived by the land or sky. This is a colour image. The position of the sun and nature of the sky suggest a morning autumnal walk on the beach. The family’s dogs are certainly present, out of frame.]

Annex: A Far Shorter Circumnavigation

Sjaelland Rundt 2019 ... a video story, written and narrated by this author with video production and reports by the skipper, Lamberto Azzi, 2019-07-05

I didn't know I had a new Homer in my crew... nice story! :-)

P.S. day one was 25-35 knots... that is why some boat lost it's mast... pushing hard has it's cost, and Ingeborg has no ambitions about "winning" whatsoever... she is a reliable, hard-core, floating brick! ;-)

The observant may note the times and legs at which the skipper passes the helm to the trimmer: always with instruction and in secure circumstances.

If you like what you read here, you can please the author by sharing it.

Copyright and Licensing

This work is strictly copyright 2022 by the author. Please share the work. Republishing requires prior written authorization. This publication contains numerous original works by the author and other members of family.

With gratitude to the Azzi family, the Australian War Memorial and the Hydrographic Office of the Royal Australian Navy.